Photo: Linh Pham/Getty Images

Employees produce protective face masks on February 6, 2020, in Thai Nguyen City, Vietnam. Manufacturing as a share of GDP is highest in Vietnam, and we are starting to see a slowdown of exports in Vietnam, as growth in July decelerated.

COVID-19 is raging across the five ASEAN countries, and the reliance on mobility suppression to control the virus is taking a toll on economic activities, from manufacturing to services. The sharp contraction and under-performance of the region’s July manufacturing activity highlights the severity of the disruption, which is likely to last longer as Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia and Thailand in particular lag on vaccination rates.

COVID-19 is raging across the five ASEAN countries, and the reliance on mobility suppression to control the virus is taking a toll on economic activities, from manufacturing to services. The sharp contraction and under-performance of the region’s July manufacturing activity highlights the severity of the disruption, which is likely to last longer as Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia and Thailand in particular lag on vaccination rates.

We expect a sharp downward movement of private consumption with inadequate fiscal and monetary support. There are a few reasons for this: Firstly, monetary conditions are already loose, and domestic currencies are weaker, limiting room for central banks to deliver more easing. Secondly, their fiscal positions are deteriorating on the revenue side, and policymakers need to avoid further credit rating agencies downgrades.

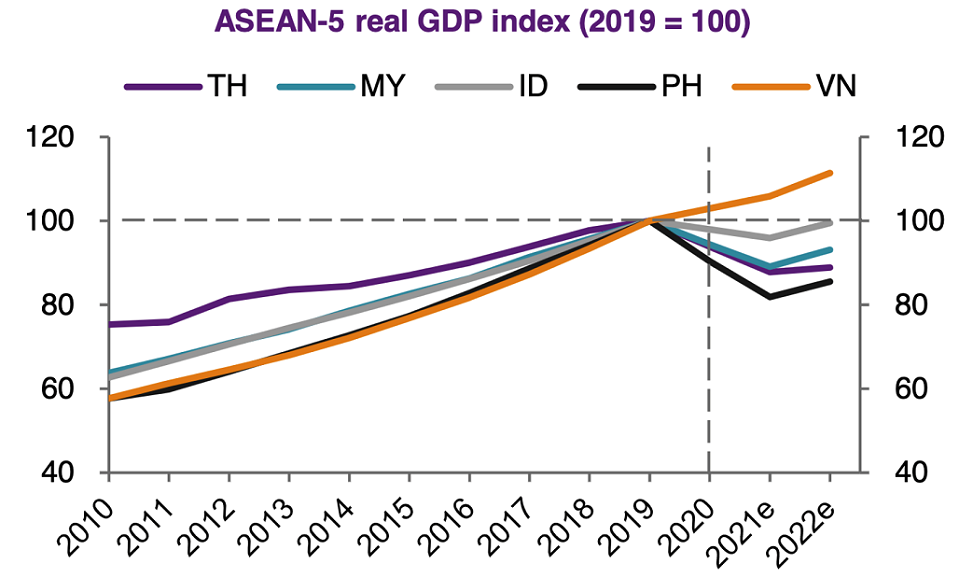

We have downgraded our expectations of 2021 GDP growth for the region from an average 5.2% to 3.8% in 2021.

Vietnam Seeing Biggest Decline

Vietnam faces the sharpest reduction — 3% of GDP — to grow at 5.2%. This is because Vietnam stands out as the country with both a reduction in domestic demand and external disruption from having the largest share of manufacturing exports to GDP of any of the countries, nearly 90%. Thailand and Malaysia’s downgrades are less severe, as they have more fiscal capacity and will likely see faster normalization, especially Malaysia with its high vaccination rates.

Source: CEIC, Natixis

The sharp underperformance of ASEAN countries’ manufacturing in July highlights the difficulty of the region in both controlling the virus and sustaining economic growth at the same time.

The question is whether there is monetary and fiscal support to mitigate the fallout. With a weaker foreign exchange from a divergence in performance with the U.S. and North Asia, Southeast Asian central banks, particularly those with high external debt liability such as Indonesia, have limited appetite to lower rates.

Even the Philippines, which had previously stated that it would cut its reserve requirement ratio, had to backtrack on that, as the peso weakened sharply recently.

No Fiscal Stimulus Likely

Facing an outlook downgrade and estimates of wider deficits, it is very unlikely that Indonesia’s expenditure in the region will rise enough to make up for the shortfall. This is why the government is trying to raise revenue via tax reforms, which would have a tightening impact on consumption.

The Philippines, too, is likely to offer meager support, as it resists pressures on credit rating agencies on further downgrades. In other words, these current account deficit economies are likely to keep expenditure on the “prudent” side, given the revenue shortfall from weaker economic output due to suppression.

Even places that announced cash handout measures such as Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore have not been able to offset the relative decline in their economic activity. Malaysia, for example, is disbursing 10 billion in Malaysian ringgit ($2.3 billion) in cash handouts to people, and Thailand approved an additional $4.5 billion or 0.9% of its GDP in the form of cash handouts and rebates to mitigate suppression measures. In Vietnam, the government is mulling a $1 billion support package in discretionary measures (reducing tax and fees for businesses).

With domestic demand weakened because of reduced mobility and limited policy support, exports are even more key. So far in the first half (H1) of 2021, shipments have done well thanks to a resurgence of demand in the U.S., Europe and China. The rise of exports is also reflected in higher investment growth of the region in H1 2021.

Manufacturing Challenges Will Impact Exports

While demand is expected to hold up in the U.S. as well as China, albeit with a deceleration, a slowdown in exports in ASEAN, especially in manufacturing, is still expected due to onshore production challenges. As such, this time around, the economies with a higher share of labor-intensive manufacturing that requires in-person contact will be disproportionately affected by social distancing measures.

Additionally, for manufacturers, higher raw material prices are raising input price costs while domestic demand leaves limited space to pass on the costs to consumers.

Vietnam has the highest share of manufacturing as a share of GDP, followed by Malaysia and Thailand. The Philippines has the least manufacturing export exposure in value, and we are starting to see a slowdown of exports in Vietnam, as growth in July decelerated. We expect that to continue into August and beyond if Vietnam continues to rely on suppression measures to tame the virus and the vaccination rates remain low.

The key difference between 2020 and 2021 exports is that the suppression is affecting ASEAN-5 economies, while final goods destinations such as the U.S. and Europe remain open. In other words, most of the hiccups to exports are driven by onshore challenges, and so the length of the disruption depends on these economies normalizing their industrial activities or limiting the fallout of suppression measures.

For Vietnam’s case, the government is prioritizing industrial sectors, such as electronics, and has asked firms to create “bubbles” and give priority for vaccines, but it has yet to be able to do this across all sectors. The impact of disruption cannot be fully mitigated as other sectors, such as textile and footwear firms, must close as they have less resources to cope with the surge of the Delta variant.

However even with a lower 5.2% growth rate in 2021, Vietnam is still outperforming its ASEAN-5 peers due to its unique growth rate in 2020 when others fell. Even with faster growth rates in 2022, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand will not return to 2019’s output level.

Related themes: DISRUPTION INVESTMENT SUPPLY CHAINS

Trinh Nguyen

Trinh Nguyen

Senior Economist at NATIXIS

Trinh Nguyen is a senior economist covering emerging Asia at NATIXIS, based in Hong Kong. Trinh previously worked at HSBC as an Asia economist, and is a nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Asia Program.

The original articles can be read in the Brink’s website HERE.

Leave a Reply